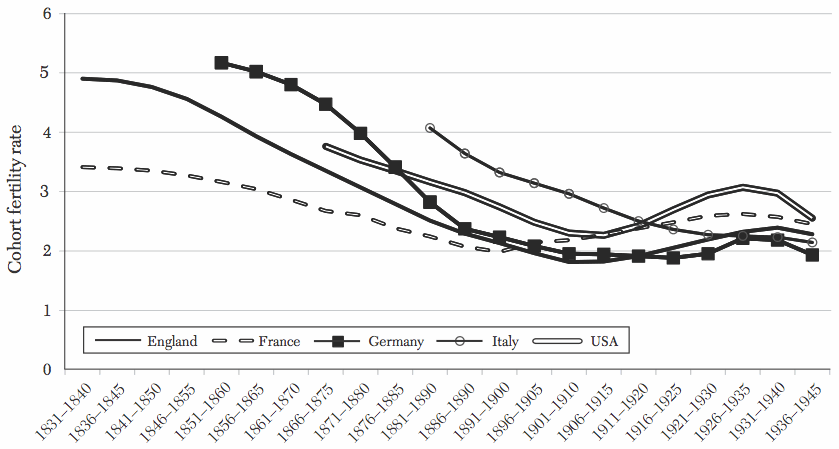

In the latest JEL, Tim Guinnane does a nice job debunking misconceptions about the great fertility fall associated with the industrial revolution. For example, “The decline in French fertility began in the late eighteenth century,” and fertility declines were not uniform across Europe:

Mortality decline doesn’t work as an explanation for fertility declines:

Fertility in the United States declined for decades before any noticeable decline in mortality.

Nor does new contraception tech:

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century, withdrawal and abstinence remained the primary approaches used by married couples. Since these technologies had been available, essentially, throughout human history, it is unlikely that the condom and similar new methods played a strong role in the fertility transition. … Methods available even prior to the fertility transition were sufficient to produce voluntary reductions of the magnitude we observe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Nor do child labor laws:

Most [child-labor] measures either did not apply to agricultural work, or did so in a more relaxed way. … German restrictions did not successfully limit the role of children in production at home, which remained important throughout the nineteenth century. And in every case, the restrictions’ impact would depend both on enforcement measures and parents’ desire to evade them. Finally, if child-labor restrictions were introduced when they were mostly irrelevant, …

Nor do new social insurance programs:

Economic ties between parents and children varied dramatically across the societies in question before the fertility transition. … At the other extreme, rural laborers’ children in England would, from at least the early-modern period, leave home for good in their early to mid teens. … social-insurance systems introduced at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century were usually replacing earlier schemes. Thus there is no clear “before.” … The broad patterns also do not make it likely that social insurance alone is central to the story. The two forerunners, France and the United States, were laggards in developing social insurance.

Still in the running, he thinks, are increases in urbanization, female employment, and gains to schooling:

Several studies document the existence of fertility control among small groups as early as the seventeenth century. These “forerunners” were usually urban elites or members of minority groups such as Jews. More generally, research based on either sub-national aggregates or micro data often find earlier fertility declines than in national data. The Princeton studies report earlier fertility declines in cities, for example. … Most studies find that urban fertility was lower than rural fertility in the nineteenth century, … Once the fertility transition began, fertility usually fell first in urban areas, with rural areas then catching up. …

Cross-sectional regressions for U.S. states in 1840 show that fertility is negatively correlated with measures of nonfarm labor-market opportunities. Once such proxies are introduced, land prices have no influence on fertility. … Crafts … finds a consistent, negative correlation between women’s [1911] local labor-force opportunities and marital fertility. …

Goldin and … Katz … find that the return to an additional year of [1915 Iowa] high school or college then was, for males, on the order of 11–12 percent. Mitch estimates the present value of acquiring literacy in Victorian Britain for a representative child. The present value of the cost of acquiring literacy would be about £4. At a wage premium of 5 shillings per week for literacy, the present value of the higher wages for a 35-year work life would be over £200.

I am looking for you argument for this, and have not found it yet: Why do you reject the opportunity-cost explanation? It seems to fit with the data in this post.

But why have land prices gone up, in your view?!