What makes a planet a good host for life? That is, what does a planet need for life to originate there and then evolve to something at the human level? Astronomers today say a planet at least needs a star that 1) lasts long enough, 2) has enough heavy elements, and 3) is not too often hit by nearby supernovae or gamma ray bursts. Using such criteria, several astronomers (mentioned below) have tried to calculate “galactic habitable zones,” i.e., galactic distributions of good-for-life planets, in both space and time. Such calculations are far more important than I had realized – they can help say how common are aliens! Let me explain.

Imagine that over the entire past and future history of our galaxy, human-level life would be expected to arise spontaneously on about one hundred planets. At least it would if those planets were not disturbed by outsiders. Imagine also that, once life on a planet reaches a human level, it is likely to quickly (e.g., within a million years) expand to permanently colonize the galaxy. And imagine life rarely crosses between galaxies.

In this case we should expect Earth to be one of the first few habitable planets created, since otherwise Earth would likely have already been colonized by outsiders. In fact, we should expect Earth to sit near the one percentile rank in the galactic time distribution of habitable planets – only ~1% of such planets would form earlier. If instead advanced life would arise on about a thousand planets, Earth should sit at the 0.1 percentile rank. And if life would arise on a thousand planets, but only one in ten such life-full planets would rapidly expand to colonize the galaxy, Earth should again sit near the one percentile rank.

Turning this argument around, if we can calculate the actual time distribution of habitable planets in our galaxy, we can then use Earth’s percentile rank in that time distribution to estimate the number of would-produce-human-level-life planets in our galaxy! Or at least the number of such planets times the chance that such a planet quickly expands to colonize the galaxy. If Earth has a low percentile rank, that suggests a good chance that our galaxy will eventually become colonized, even if Earth destroys itself or chooses not to expand. (An extremely low rank might even suggest we’ll encounter other aliens as we expand across the galaxy.) In contrast, if Earth has a middling rank, that suggests a low chance that anyone else would ever colonize the galaxy – it may be all up to us.

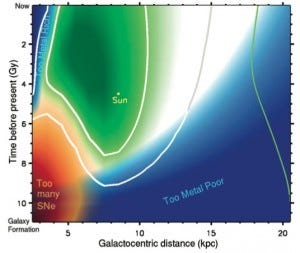

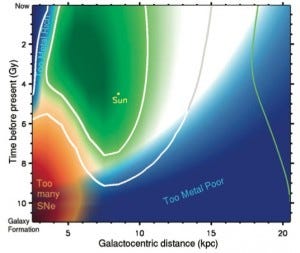

At the moment published estimates for Earth’s time percentile rank vary widely. An ’04 Science paper (built on an ’01 Icarus paper) says:

~30% of stars harboring life in the Galaxy are older than the Sun.

Except this is regarding a distribution cutoff at today. Eyeballing the distribution:

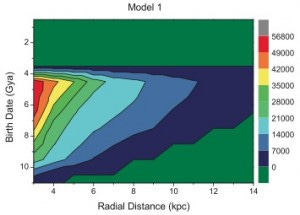

suggests Earth is at ~10-20 percentile of the total distribution. An ’11 Astrobiology paper gives a distribution of habitable planets that exist today and have existed for four billion years:

To my eye, this seems to suggest Earth is even earlier, perhaps 5-15%, as confirmed by this quote:

The [star formation rate] experienced in the last few billion years, coupled with increasing levels of metallicity, suggests that many more planets will be conducive to complex life in the future.

That paper also estimates that 80-90% of habitable planets are closer than Earth to the galactic center.

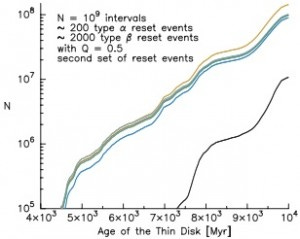

Finally this cutoff distribution from an ’10 International Journal of Astrobiology paper suggests Earth is very early:

Though that paper gives no explicit Earth date percentile.

Clearly there’s much room for progress here. But progress seems feasible, and quite valuable. With just a bit more astronomy calculation effort, we may be able to learn something substantial about just how common are aliens in spacetime!

"Why? If no extinctions occur knowledge will be preserved."

Really? I think the Romans would disagree.

"Metals don't disappear when you use them, you can recycle them so again."

Second Law of Thermodynamics? Yes, you can recycle, but each time you do so, some of the source metal will be lost.

"Abundant amounts of metals exist on every asteroid, planetoid and rocky planet out there"

True. But we can also make synthetic gasoline. The reason we don't is because it takes more energy to make gas that way than you get back from burning it. So it's not economical.

I'm not saying that interstellar colonization is impossible - just that nothing is a simple as you think. Plus, the Fermi Paradox + Von Neumann's work together seems to support the notion that interstellar colonization is extremely extremely unlikely. Else...Where is everybody?

"Over that period of time, everything will be learned and forgotten again and again."

Why? If no extinctions occur knowledge will be preserved.

"But extracting and transmitting that energy also require other natural resources (e.g. precious metals and semi-conductors, rare elements). And even on scales close to today's energy requirements - those resources are close to exhaustion. And we've been using them only a century or so. No. It's not clearly sustainable."

Metals don't disappear when you use them, you can recycle them so again, if there are enough of them in year 1 there will be enough of them in year 100 million. Abundant amounts of metals exist on every asteroid, planetoid and rocky planet out there. In the near future there will be a transition from the current state of scarce energy and abundant minerals to one of abundant energy and scarce minerals, that's when space mining will kick-off.