[Edited to remove insensitive framing. Also, the possibility of reducing the misery in factory farming with such technology does not and would not justify factory farming.]

I have spoken with a lot of people who are enthusiastic about the possibility that advanced genetic engineering technologies will improve animal welfare.

But would it really take radical new technologies to produce genetics reducing animal suffering?

Modern animal breeding is able to shape almost any quantitative trait with significant heritable variation in a population. One carefully measures the trait in different animals, and selects sperm for the next generation on that basis. So far this has not been done to reduce animals’ capacity for pain as such, or to increase their capacity for pleasure, but it has been applied to great effect elsewhere on productivity (with some positive but overall negative effects on welfare).

One could test varied behavioral measures of fear response, and physiological measures like cortisol levels, and select for them. As long as the measurements in aggregate tracked one’s conception of animal welfare closely enough, breeders could generate increases in farmed animal welfare, potentially initially at low marginal cost in other traits.

Just how powerful are ordinary animal breeding techniques? Consider cattle:

In 1942, when my father was born, the average dairy cow produced less than 5,000 pounds of milk in its lifetime. Now, the average cow produces over 21,000 pounds of milk. At the same time, the number of dairy cows has decreased from a high of 25 million around the end of World War II to fewer than nine million today. This is an indisputable environmental win as fewer cows create less methane, a potent greenhouse gas, and require less land.

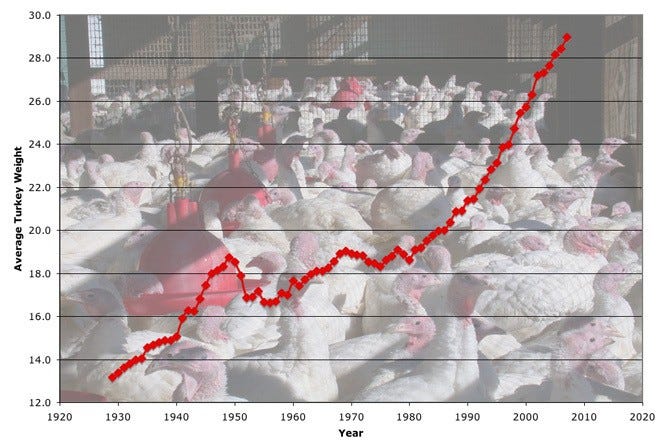

Wired has an impressive chart of turkey weight over time:

Anderson, who has bred the birds for 26 years, said the key technical advance was artificial insemination, which came into widespread use in the 1960s, right around the time that turkey size starts to skyrocket…

This process, compounded over dozens of generations, has yielded turkeys with genes that make them very big. In one study in the journal Poultry Science, turkeys genetically representative of old birds from 1966 and modern turkeys were each fed the exact same old-school diet. The 2003 birds grew to 39 pounds while the legacy birds only made it to 21 pounds. Other researchers have estimated that 90 percent of the changes in turkey size are genetic.

Moreover, breeders are able to improve complex weighted mixtures of diverse traits:

The bull market (heh) can be reduced to one key statistic, lifetime net merit, though there are many nuances that the single number cannot capture. Net merit denotes the likely additive value of a bull’s genetics. The number is actually denominated in dollars because it is an estimate of how much a bull’s genetic material will likely improve the revenue from a given cow. A very complicated equation weights all of the factors that go into dairy breeding and — voila — you come out with this single number. For example, a bull that could help a cow make an extra 1000 pounds of milk over her lifetime only gets an increase of $1 in net merit while a bull who will help that same cow produce a pound more protein will get $3.41 more in net merit. An increase of a single month of predicted productive life yields $35 more.

No futuristic technologies are needed to make progress, although they would expedite the process: just feed accurate enough measurements of animal welfare into the net merit equation and similar progress could begin on the new trait.

Added December 8th:

Gaverick Matheny reports that some breeds have been selected in part for welfare. However, because breeders have not yet finished optimizing farm animals for productivity, the opportunity cost of not increasing productivity even further instead has been too high, given weak market and other pressures for welfare improvement, for this to take off.

Domestication doesn't mean docility: it means a suite of traits such as much better social learning skills, neoteny, etc. Consider guard dogs or hunting dogs. A generalized 'docility' would defeat the point entirely - what we want are dogs which are extremely docile in some respects (not attacking a stranger its master is shaking hands with and letting into the house, or letting the owner's baby pull on its ears) and as aggressive as possible in others (against strangers towards which its master is exhibiting fear/aggression, or towards rabbits), and able to learn the difference such as by developing a better theory of mind, being able to understand eye gazes, having longer periods of mental plasticity etc.

This also doesn't address dynamics within the groups: there is not too much benefit to very docile chickens, and too-docile chickens may be at severe disadvantages inside the barn when competing/interacting with other 'domesticated' chickens. Not to mention the serious consequences that can attend reducing or eliminating pain entirely, as experienced by lepers, diabetics, or people with pain asymbolia.

That assumes that the utility we would gain from better evolutionary adaptiveness outweighs the disutility of ignoring how our desires extrapolate, which seems highly unlikely.