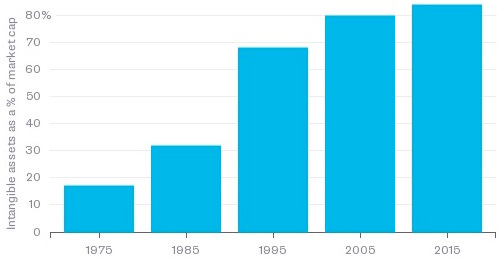

We all know that the capital-intensive businesses of yesteryear like GM and US steel are an increasingly small share of the US economy. But until I saw this post by Justin Fox I had no idea how dramatic the transformation had been since 1975:

Wow. I had no idea as well. As someone who teaches graduate industrial organization, I can tell you this is HUGE. And I’ve been pondering it for the week since Scott posted the above.

Let me restate the key fact. The S&P 500 are five hundred big public firms listed on US exchanges. Imagine that you wanted to create a new firm to compete with one of these big established firms. So you wanted to duplicate that firm’s products, employees, buildings, machines, land, trucks, etc. You’d hire away some key employees and copy their business process, at least as much as you could see and were legally allowed to copy.

Forty years ago the cost to copy such a firm was about 5/6 of the total stock price of that firm. So 1/6 of that stock price represented the value of things you couldn’t easily copy, like patents, customer goodwill, employee goodwill, regulator favoritism, and hard to see features of company methods and culture. Today it costs only 1/6 of the stock price to copy all a firm’s visible items and features that you can legally copy. So today the other 5/6 of the stock price represents the value of all those things you can’t copy.

So in forty years we’ve gone from a world where it was easy to see most of what made the biggest public firms valuable, to a world where most of that value is invisible. From 1/6 dark matter to 5/6 dark matter. What can possibly have changed so much in less than four decades? Some possibilities:

Error – Anytime you focus on the most surprising number you’ve seen in a long time, you gotta wonder if you’ve selected for an error. Maybe they’ve really screwed up this calculation.

Selection – Maybe big firms used to own factories, trucks etc., but now they hire smaller and foreign firms that own those things. So if we looked at all the firms we’d see a much smaller change in intangibles. One check: over half of Wilshire 5000 firm value is also intangible.

Methods – Maybe firms previously used simple generic methods that were easy for outsiders to copy, but today firms are full of specialized methods and culture that outsiders can’t copy because insiders don’t even see or understand them very well. Maybe, but forty years ago firm methods sure seemed plenty varied and complex.

Innovation – Maybe firms are today far more innovative, with products and services that embody more special local insights, and that change faster, preventing others from profiting by copying. But this should increase growth rates, which we don’t see. And product cycles don’t seem to be faster. Total US R&D spending hasn’t changed much as a GDP fraction, though private spending is up by less than a factor of two, and public spending is down.

Patents – Maybe innovation isn’t up, but patent law now favors patent holders more, helping incumbents to better keep out competitors. Patents granted per year in US have risen from 77K in 1975 to 326K in 2014. But Patent law isn’t obviously so much more favorable. Some even say it has weakened a lot in the last fifteen years.

Regulation – Maybe regulation favoring incumbents is far stronger today. But 1975 wasn’t exact a low regulation nirvana. Could regulation really have changed so much?

Employees – Maybe employees used to jump easily from firm to firm, but are now stuck at firms because of health benefits, etc. So firms gain from being able to pay stuck employees due to less competition for them. But in fact average and median employee tenure is down since 1975.

Advertising – Maybe more ads have created more customer loyalty. But ad spending hasn’t changed much as fraction of GDP. Could ads really be that much more effective? And if they were, wouldn’t firms be spending more on them?

Brands – Maybe when we are richer we care more about the identity that products project, and so are willing to pay more for brands with favorable images. And maybe it takes a long time to make a new favorable brand image. But does it really take that long? And brand loyalty seems to actually be down.

Monopoly – Maybe product variety has increased so much that firm products are worse substitutes, giving firms more market power. But I’m not aware that any standard measures of market concentration (such as HHI) have increased a lot over this period.

Alas, I don’t see a clear answer here. The effect that we are trying to explain is so big that we’ll need a huge cause to drive it. Yes it might have several causes, but each will then have to be big. So something really big is going on. And whatever it is, it is big enough to drive many other trends that people have been puzzling over.

Added 5p: This graph gives the figure for every year from ’73 to ’07.

Added 8p: This post shows debt/equity of S&P500 firms increasing from ~28% to ~42% from ’75 to ’15 . This can explain only a small part of the increase in intangible assets. Adding debt to tangibles in the numerator and denominator gives intangibles going from 13% in ’75 to 59% in ’15.

Added 8a 6Apr: Tyler Cowen emphasizes that accountants underestimate the market value of ordinary capital like equipment, but he neither gives (nor points to) an estimate of the typical size of that effect.

Morgan is expressing my thoughts on the matter as well (better than I could). I see us as entering a world of free and virtual, where economics no longer applies-- at least not in the same way.

Just about everything I do is free and/or virtual. Every year I do more free or near free (and it gets better) and spend less on physical things.

Two examples: twenty years ago my company built a teleconference room in every region. The cost was about a third of a million plus a hundred grand or so annually in upkeep and maintenance. This was to eliminate the costs of air travel. Today I have a better teleconference system included as a free app on every smart device in my house. I have millions of dollars in teleconferencing utility and it shows up as near zero in economics measures. It subtracted from GDP!

Second, I used to buy an album or two a month at $8 or $9 each in the late seventies. Today for $15 a month I get a virtual library in CD quality which includes over twenty million albums. Better quality, portable and more convenient. This would have cost millions to buy and store twenty years ago. Today, better for less.

Economists are simply missing what is going on right under their feet. Stagnation my ass.

How fine-tuned are HHI indices?

For example, analysts consider Fabrinet an "electronics contract manufacturer", a massive industry 1,000 times larger than Fabrinet. But in fact they're an optical component manufacturer with 50% market share, sole supplier on most everything they do, win deals w/ out bids, etc.

Another: Mocon is superficially an Industrial Instrumentation firm. In fact, their instruments do one thing: measure the rate at which substances permeate materials, which is useful in food packaging. They must have more than 50% share of this space, if not 90%.

Defining market segments accurately is extremely difficult for industry insiders to do; they've got little incentive to publicize their findings; and as Peter Thiel points out, those w/ near monopoly power tend to exaggerate the scope of their market to fend off regulatory attention.

Wonder whether HHI's ability to carve the economy at its joints has deteriorated.