Most biological species specialize for particular ecological niches. But some species are generalists, “specializing” in doing acceptably well in a wider range of niches, and thus also in rapidly changing niches. Generalist species tend to be more successful at generating descendant species. Humans are such a generalist species, in part via our unusual intelligence.

Today, firms in rapidly changing environments focus more on generality and flexibility. For example, CEO Andy Grove focused on making Intel flexible:

In Only the Paranoid Survive, Grove reveals his strategy for measuring the nightmare moment every leader dreads–when massive change occurs and a company must, virtually overnight, adapt or fall by the wayside–in a new way.

A focus on flexibility is part of why tech firms tend more often to colonize other industries today, rather than vice versa.

War is an environment that especially rewards generality and flexibility. “No plan survives contact with the enemy,” they say. Militaries often lose by preparing too well for the last war, and not adapting flexibly enough to new context. We usually pay extra for military equipment that can function in a wider range of environments, and train soldiers for a wider range of scenarios than we train most workers.

Centralized control has many costs, but one of its benefits is that it promotes rapid thoughtful coordination. Which is why most wars are run from a center.

Familiar social institutions tend to be run by those who have run parts of them well recently. As a result, long periods of peace and stability tend to promote specialists, who have learned well how to win within a relatively narrow range of situations. And those people tend to change our rules and habits to suit themselves.

Thus rule and habit changes tend to improve performance for rulers and their allies within the usual situations, often at the expense of flexibility for a wider range of situations. As a result, long periods of peace and stability tend to produce fragility, making us more vulnerable to big sudden changes. This is in part why software rots, and why institutions rot as well. (Generality is also often just more expensive.)

Through most of the farming era, war was the main driver pushing generality and flexibility. Societies that became too specialized and fragile lost the next big war, and were replaced by more flexible competitors. Revolutions and pandemics also contributed.

As the West has been peaceful and stable for a long time now, alas we must expect that our institutions and culture have been becoming more fragile, and more vulnerable to big unexpected crises. Such as this current pandemic. And in fact the East, which has been adapting to a lot more changes over the last few decades, including similar pandemics, has been more flexible, and is doing better. Being more authoritarian and communitarian also helps, as it tends to help in war-like times.

In addition to these two considerations, longer peace/stability and more democracy, we have two more reasons to expect problems with inflexibility in this crisis. The first is that medical experts tend to think less generally. To put it bluntly, most are bad at abstraction. I first noticed this when I was a RWJF social science health policy scholar, and under an exchange program I went to the RWJF medical science health policy scholar conference.

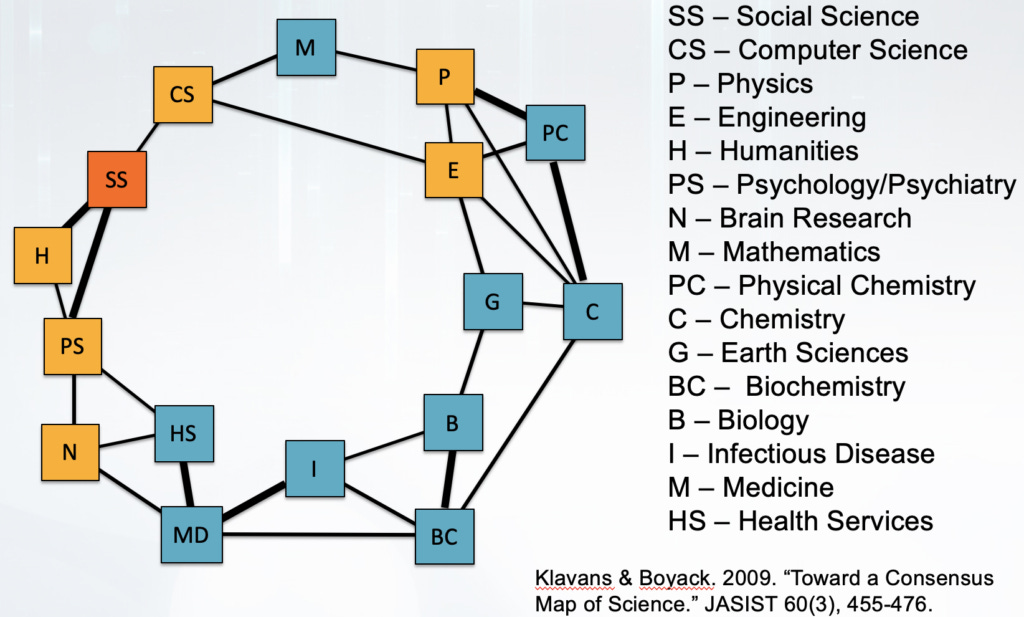

Biomed scholars are amazing in managing enormous masses of details, and bringing up just the right examples for any one situation. But most find it hard to think about probabilities, cost-benefit tradeoffs, etc. In my standard talk on my book Age of Em, I show this graph of the main academic fields, highlighting the fields I’ve studied:

Academia is a ring of fields where all the abstract ones are on one side, far from the detail-oriented biomed fields on the other side. (I’m good at and love abstractions, but have have limited tolerance or ability for mastering masses of details.) So to the extent pandemic policy is driven by biomed academics, don’t expect it to be very flexible or abstractly reasoned. And my personal observation is that, of the people I’ve seen who have had insightful things to say recently about this pandemic, most are relatively flexible and abstract polymaths and generalists, not lost-in-the-weeds biomed experts.

The other reason to expect a problem with flexibility in responding to this pandemic is: many of the most interesting solutions seem blocked by ethics-driven medical regulations. As communities have strong needs to share ethical norms, and most people aren’t very good at abstraction, ethical norms tend to be expressed relatively concretely. Which makes it hard to change them when circumstances change rapidly. Furthermore we actually tend to punish the exceptional people who reason more abstractly about ethics, as we don’t trust them to have the right feelings.

Now humans do seem to have a special wartime ethics, which is more abstract and flexible. But we are quite reluctant to invoke that without war, even if millions seem likely to die in a pandemic. If billions seemed likely to die, maybe we would. We instead seem inclined to invoke the familiar medical ethics norm of “pay any cost to save lives”, which has pushed us into apparently endless and terribly expensive lockdowns, which may well end up doing more damage than the virus. And which may not actually prevent most from getting infected, leading to a near worst possible outcome. In which we would pay a terrible cost for our med ethics inflexibility.

When a sudden crisis appears, I suspect that generalists tend to know that this is a potential time for them to shine, and many of them put much effort into seeing if they can win respect by using their generality to help. But I expect that the usual rulers and experts, who have specialized in the usual ways of doing things, are well aware of this possibility, and try all the harder to close ranks, shutting out generalists. And much of the public seems inclined to support them. In the last few weeks, I’ve heard far more people say “don’t speak on pandemic policy this unless you have a biomed Ph.D”, than I’ve ever in my lifetime heard people say “don’t speak on econ policy without an econ Ph.D.” (And the study of pandemics is obviously a combination of medical and social science topics; social scientists have much relevant expertise.)

The most likely scenario is that we will muddle through without actually learning to be more flexible and reason more generally; the usual experts and rulers will maintain control, and insist on all the usual rules and habits, even if they don’t work well in this situation. There are enough other things and people to blame that our inflexibility won’t get the blame it should.

But there are some more extreme scenarios here where things get very bad, and then some people somewhere are seen to win by thinking and acting more generally and flexibly. In those scenarios, maybe we do learn some key lessons, and maybe some polymath generalists do gain some well-deserved glory. Scenarios where this perfect storm of inflexibility washes away some of our long-ossified systems. A dark cloud’s silver lining.

If you look at his background, the answer is no. He is just a doctor with a sociology Ph.D.

As you surely know, I pointed to a substantial likelihood that we will do more lockdown than is best. I did not claim that zero lockdown was the optimal policy.