Can money buy oranges? Well obviously, in an indirect sense. With money, you could travel to a place where you’ve heard oranges grow wild, search to find such a plant in the wild, dig it up and try to ship it home, see if it you can make it thrive there, and if it does, take some oranges as your reward. This might work, but success depends not just on the money you pay; it also depends much more on your effort, abilities, and other context. In principle, you might be able to execute this plan without any money, but typically more money will make such a plan a bit easier. So, yes, in this weak sense, you can “buy” oranges with money.

At an ordinary grocery store, however, you can buy oranges much more directly. You go to the produce section, look for the orange color, walk to the pile of oranges, take as many as you want, and pay the price per orange at the register. Or at a full service grocery, you might just say “six oranges please” and a grocer would go find and bag them for you. Online, you might just type in “orange”, enter “6” for quantity, and click “buy”.

These ways to buy oranges are usually pretty reliable even for an ordinary person who knows little about oranges. Using these methods, the number of oranges you get depends mainly on how much money you are willing to pay, and much less on other context. This is what I mean by buying something “directly.” And so regarding the oft-asked question “what can money buy?”, a more interesting version of this question is “What can money buy relatively directly.”

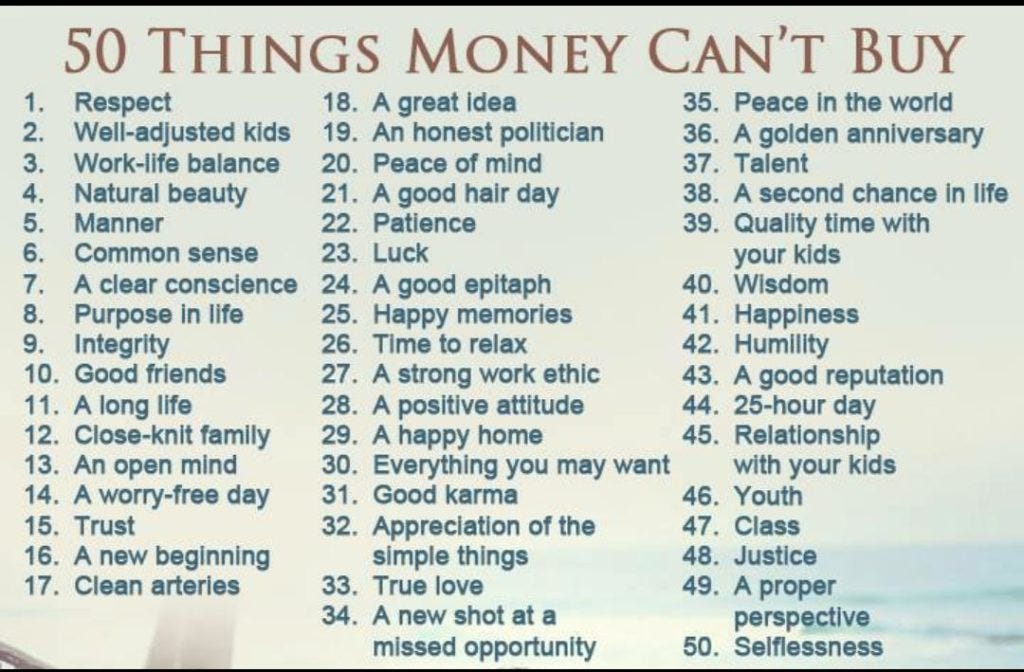

As more money makes most any plan a bit easier to achieve, the many long lists one can find of “things money can’t buy” are in one sense obviously wrong; money helps with most of them. And if they just mean that money can’t guarantee the max level of each thing, that’s obvious, but trivial, as pretty much nothing guarantees that. You can’t even guarantee you’ll get oranges if you order them from a grocery. And if that is the meaning, why pick on money, relative to anything else that might greatly but imperfectly help you get things?

Perhaps what people mean is that money isn’t the main factor that determines if you succeed with such things; money can be a distraction from more important issues. But if so, that seems to claim that you can’t buy such things directly. Which then raises the key question: for what kinds of things can the money you pay be a strong factor in determining how much of it you get? That is, what can money buy directly?

In my last post, I talked about how one can buy higher wages, via a job agent. I wasn’t saying that there are complex and subtle ways to spend money to help your career, ways that could work if only you were clever and skilled enough to understand and apply them. I was instead saying that there is a simple direct way to do this, one most anyone can understand: hire an agent (and anti-agent). That method doesn’t guarantee you any particular wage, but it does let you control how much you pay per wage increase.

In fact, I’ll go further now, and say that there seem to be ways to measure most anything, and as a result we can buy most any measured thing relatively simply and directly. That is, via a simple method that most anyone can come to understand, you can just point to what you want, put cash on the table, and then lose cash in proportion to how much you get of what you want. And the relation is substantially causal; paying more can cause you to get more, even when you have little relevant ability or understanding.

In the academic literature, this method is called an “incentive contract”. You find a way to measure the outcome you want, you offer to give someone access to levers by which they can plausibly influence this outcome, and you contract to pay them more cash the higher is this measure. You might also hold auctions or competitions to see who is best to put into this role.

We have a great many real examples today, and in history, of oft-used incentive contracts. Artists and athletes have agents paid a fraction of their earnings. Line workers are paid “piece rates” per how many items they assemble, or tomatoes they pick. Sales workers are paid commissions, per how many items they sell. Hedge fund managers are paid more if their fund makes higher returns. Lawyers on contingency fees are paid a fraction of court awarded damages. Firm managers are paid in stocks and options which rise in value when firm stock prices rise. Athletes are paid bonuses for individual and team success. Construction contractors are paid more if their work is completed by a deadline. Ships carrying convicts to Australia were paid on the number who arrived alive (which worked much better than the number who started out alive.)

Are the applications we’ve seen the only feasible ones, or could many more yet be developed? Consider beauty. Some say beauty can’t be measured, as it is “in the eye of the beholder”. But if you ask many people to rate someone’s beauty, their ratings are correlated. So imagine taking many standardized pictures and video of a client, across across their usual range of clothes and environments, and then paying many independent observers to rate their attractiveness. Do this at the start to get an initial value, and plan to do it again in, say, six months. A client might pay a beauty agent based on the change in this measure.

Potential beauty agents could bid by offering how much money they want to be paid per unit of increased beauty, how much they would pay up front to gain this role, and which particular beauty decisions they want to control, rather than merely advise, at least until the second measurement. There are probably clever ways to use auctions or decision markets to select from among these bids, but such details need not concern us now.

Yes, it would be a problem if a beauty agent could corrupt beauty measurements, or exploit their biases. But if such effects are modest, expert beauty agents can likely substantially increase a client’s beauty, relative to that client’s amateur efforts. Consider that movies don’t usually let actors pick their own clothes and hairstyle to look good in each movie; beauty experts instead make those choices. Yes, clients may care less about beauty as seen by average people, and more as seen by particular communities. But measuring such local versions of beauty should only cost a bit more.

Now consider happiness. If happiness were an entirely internal mental state that never influenced our external appearances, well then yes it would be hard to measure happiness. At least until we can better read brains. But most humans leak their feelings in many ways. So a 24/7 audio/video feed of a person, especially their facial expression and tone of voice, perhaps augmented by watch-based measures of heart rates, etc., seems plenty sufficient. Especially if processed via self and other reports, rather than artificially. Happiness could be measured pretty accurately from such things, especially for a client who wants it to be measurable, so that they can hire an agent to increase their happiness. (And especially as things like smiles and laughter probably evolved to signal happy internal states.)

A happiness agent is given control over some elements of a client’s life, and can advise on others. Especially on which other agents to hire for beauty, health, career, etc. Happiness agents pay some initial fee to gain this role, and then they are paid in proportion to the client’s measured happiness. Such agents might be big firms that combine many kinds of happiness expertise, and who can take big risks. If there are things that an expert can learn about how to be happy, things an ordinary amateur doesn’t know, then there is likely substantial scope for using agents to directly buy happiness. If so, money can buy happiness, directly.

Well this is enough for one blog post. The key conclusion: it looks feasible to much more directly buy many things we care greatly about, including beauty, happiness, health, career success, popularity, and status. Yes it would be work to set up systems to measure such things, work that could not be recouped for just from one client. But the prospect of many millions of clients should be quite sufficient.

One key question remains: why hasn’t there been more interest in such possibilities? Are these new innovations that could spread widely, or are they blocked by key fundamental permanent obstacles not yet considered in the above discussion?

Added 20Apr: Most seem to actually be comforted by the fact that it can be hard to buy things with money, and seem uninterested in finding ways to make it easier to buy things with money. I suspect they feel that better methods of this sort would give a relative advantage to people with more money, who they see as other people. While everyone could benefit from better ways to buy things with money, that matters little to those focused on relative status.

I think that some people pursue money and then spend it all on status signals, and that this is not a good life. I also think this has been generally acknowledged that this is a sort of addictive vice like drugs or gambling. Therefore, people are motivated to talk about how you shouldn't do it, the same way they say things like "crack is wack" or "crime doesn't pay". So one explanation for talk about what money can't buy is part of this genre of warnings about a vice. With that in mind it's surprising to me that the list you reposted includes "47. Class." I would have thought that the whole point of this list was to warn against pursuing money to spend on status symbols, which is sort of like spending it on class.

Measuring someone's internal emotional state seems particularly vulnerable to corruption to me, at least on the face of it. i.e. relative to other things we want to measure, with internal emotional state it seems particularly hard to find reliable signs of that state which are hard for the person in question to fake. Due to the fact that they are all mediated by the person in question. (Though of course we might be able to find some signs for which faking is costly enough to stop it....)

But I'm probably missing something. What are some examples you have in mind of other things that are equally easy to corrupt the measurement of and yet which we successfully measure?