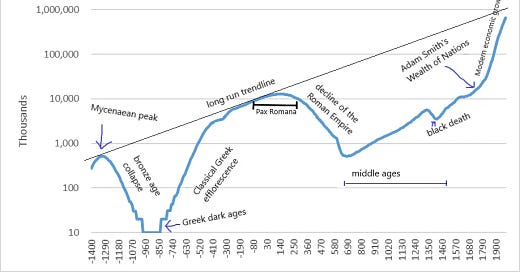

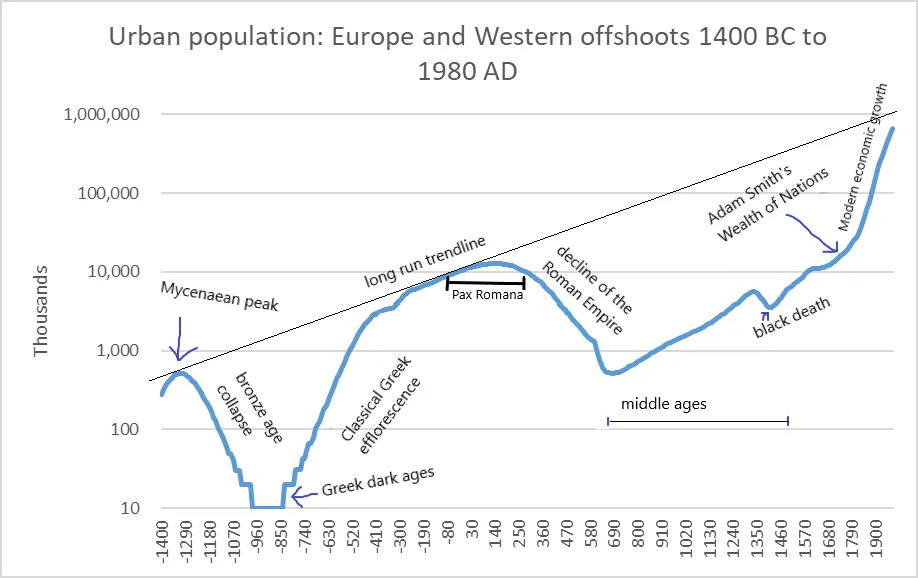

This graph of European urban population over history shows some dramatic declines, suggesting that there may have been historical analogue to our upcoming world population decline. And there have long been rumors that at least elites often had low fertility. Searching for quotes, I’ve found these:

Classical literary sources, tombstone inscriptions and skeletal remains have been used by classicists to show that there was probably a decline in the population of the Roman Empire caused by the deliberate control of family numbers through contraception, infanticide, and child exposure.…

If the modern fertility transition … is not unique, then its most likely predecessors were probably found in the classical period, especially in Ancient Rome, or in Soong China or Tokugawa Japan. …

Where the literary evidence is strongest is that there was a significant restriction of legitimate fertility in upper-class society [in ancient Rome]. That there was such a phenomenon is given greater strength by agreement, both ancient and modern, on why it should have taken place, namely fear of dividing the family patrimony among the heirs, so inevitably demoting them and their children down the social and economic ladders. This would have meant one section of the society exhibiting long-term but probably stable lower fertility.

This may not have been a rare phenomenon in history. It may well have been the situation among the Genevese bourgeoisie in the eighteenth century. It may have been the situation in France that resulted from the equal inheritance promoted by the revolutionary army and the statutes of the Code Napoleón, a phenomenon possibly misinterpreted because the French fertility decline was caught up by the emerging global fertility transition induced by the Industrial Revolution. (more)

Europeans report[ing] on Asian infanticide … were surprised that infanticide occurred not only within marriage but among the rich as well as the poor. … Infanticide, even when not proscribed, usually had an element of secrecy, … Bangladesh … mortality rates showed a preference for a family consisting of two sons and one daughter. … East India Company officials noted with surprise that infanticide in India was practised not by the poor but by the rich …

Family pride was, and is, strongly associated with the ability to pay cripplingly high dowries. … All this is propelled by … aim of subcastes to be seen to behave as higher subcastes, … In the top rungs of these castes the daughters could not marry higher and so the only way to avoid the degrading shame of having a postpubertal unmarried daughter in the family was to kill her at birth. The East India Company’s reports recorded such subclans as claiming that no daughter had been raised for generations. …

Tokugawa [Japan] near-stationary population was achieved with lower marital fertility but higher marriage levels than in England at the same time. Lower marital fertility was partly attained by infanticide, although this was probably practised mostly in families with above-average fertility or below-average child mortality. It probably ensured a lower level of difficulty over land inheritance and fewer other siblings seeking work off the family farm and outside agriculture. …

From his field work on the lower Yangtze in 1936, spoke of infanticide being common at that time especially when small landholders were faced with the problem of land division. … The evidence is clear that the main fear in having too many sons was the division of the land in a male partible inheritance system to the point where the sons cannot grow enough food for their families’ needs. … Sons beyond the second were so disadvantageous that they were often given away; …

The expanding West with its denial of the right to kill a child was deeply shocked on encountering large-scale [Asian] infanticide.… decision to kill is usually made by the father, … women are more likely to reveal what happens, partly because many are aggrieved. The act is nearly always carried out by women. …

There is usually a desire to improve one’s situation or that of the family or to ensure that one’s descendants are not poorer. Female infanticide was greatest among the richest in eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century India. …

Situation was identical among the middle class in ancient Rome and probably among the late eighteenth-century and nineteenth- century French peasantry. The lowest subcastes in India’s hypergamous castes could not afford dowry for the marriages of more than one daughter. (more)

Added 29Mar2025:

Aristotle Politics II.9 :

The mention of avarice naturally suggests a criticism on the inequality of proprty. While some of the Spartan citizens have quite small properties, others have very large ones: hence the land has passed into the hands of a few. And this is due also to faulty laws; for, although the legislator rightly holds up to shame the sale or purchase of an inheritance, he allows anybody who likes to give or bequeath it. Yet both practices lead to the same result. And nearly two-fifths of the whole country are held by women; this is owing to the number of heiresses and to the large dowries which are customary. It would surely have been better to have given no dowries at all, or, if any, but small or moderate ones. As the law now stands, a man may bestow his heiress on any one whom he pleases, and, if he die intestate, the privilege of giving her away descends to his heir. Hence, although the country is able to maintain 1500 cavalry and 30,000 hoplites, the whole number of Spartan citizens fell below 1000. The result proves the faulty nature of their laws respecting property; for the city sank under a single defeat; the want of men was their ruin. There is a tradition that, in the days of their ancient kings, they were in the habit of giving the rights of citizenship to strangers, and therefore, in spite of their long wars, no lack of population was experienced by them; indeed, at one time Sparta is said to have numbered not less than 10,000 citizens. Whether this statement is true or not, it would certainly have been better to have maintained their numbers by the equalization of property. Again, the law which relates to the procreation of children is adverse to the correction of this inequality. For the legislator, wanting to have as many Spartans as he could, encouraged the citizens to have large families; and there is a law at Sparta that the father of three sons shall be exempt from military service, and he who has four from all the burdens of the state. Yet it is obvious that, if there were many children, the land being distributed as it is, many of them must necessarily fall into poverty.

Citizenship required some min amount of wealth, which fewer people could meet due to dividing wealth up among so many kids. HT Arnold Brooks.

Many of these examples seem to correlate with resource limitations. In an agrarian society, if the amount of land is limited, increasing population leads to privation. This may be expressed in terms of not wanting to divide land to maintain status, but if there are more people on the same amount of land, with static technology, they will all be poorer and eventually starve. Describing this as a fundamentally social process rather than a social response to resource constraints seems like a reach.

Modern technological societies are built on childhood education. This puts economic stress on parents, both because education itself is expensive and because children are no longer a source of income. Such societies also use the production of women, reducing the amount of time women can devote to childrearing, further increasing the downward pressure on fertility. All of this would be true, regardless of social norms, so it seems odd to claim that social norms drive this, in preference to this being the social response to changing conditions.

Beyond that, at least some of the concern over this trend comes from a belief that unless the workforce keeps growing, technology will stagnate and progress will cease. If that is the case, however, removing women from the workforce in order to increase fertility would have the same effect.

My own expectation is that we will find a series of technological improvements (increased longevity, more efficient fertility and childrearing, improved allocation of resources) that will stabilize the population and maintain technological (defined broadly) progress. Whether population increases at that point will probably depend on how well we have addressed the other needs (land, waste, and energy) that constrain human population.

You should take a look at Augustus’s Moral Laws (Lex Julia). He’s often described as a devout social conservative (aristocratic, traditional Roman virtue and family structure), and the laws lend credence to that. They offer a glimpse of what Augustus thought had changed amongst his peers. They don’t seem to have worked in the long run (which is informative if we’re thinking about where to make the changes), and many were repealed soon after his death.